Found Drowned: Emily Louise Chambers (1865-1897) and Eva Louise Chambers (1896-1897)

The story of Emily Louise Chambers and her baby Eva Louise Chambers who were found drowned in 1897.

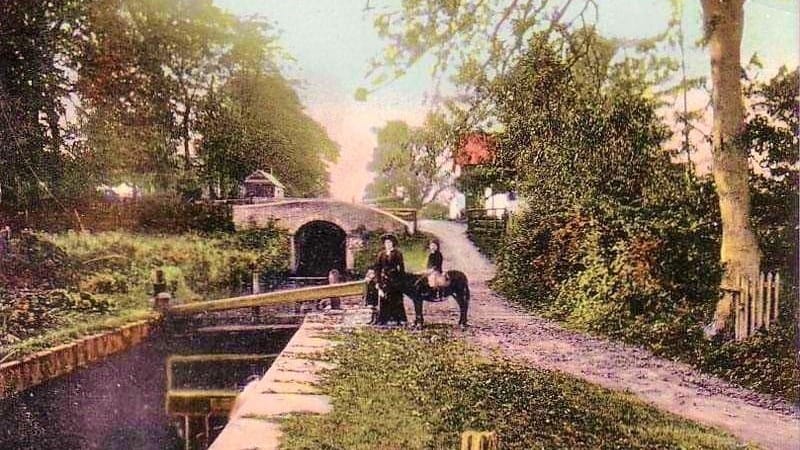

This story comes from the southernmost end of the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal, on the outskirts of Newport, in Monmouthshire, South Wales.

Friday the 22nd of January 1897 was a bitterly cold and windy winter’s morning. Shortly before nine o’clock, a well turned out young woman with a baby in her arms was walking along the bank of the Canal near Malpas Road. The canal here wound away from the town centre, and it would have been unusual for a well-to-do young woman to be here at such an early hour, and in such cold weather. A bricklayer named James noticed her from a field away. Although his curiosity was piqued, and he admitted that he would have spoken to her had he been closer, he noticed nothing sufficiently unusual in her behaviour to persuade him to cross the field to speak to her. The young woman continued on her way, and James thought no more of it. (This was James Atkinson, Hodgkinson or Hotchkinson, of 59 Redland Street, who went on to give evidence during the inquest).

About half an hour later, a 34 year old bargeman, John Henry Jones, of Canal Bank, Cefn, was bringing a bargeload of bricks along the canal for Allt-yr-yn. When he neared the lime kiln (probably the Lime Works near Crindau Bridge) he noticed a body floating in the water just in front of the barge. Before he could bring his barge to a standstill, the body had been washed towards the canal bank.

Using a boathook, John Jones and William Price, a labourer from Reform Buildings, lifted the young woman’s body onto the bank. James returned at that moment, and he recognised the body as the young woman he had spotted earlier. He immediately told John and William that there had been a baby with her. They fetched Police Constable Drewitt, of the borough police force, grappling irons were procured, and a messenger was despatched to the Town Hall for the ambulance. The body of the baby, about six weeks old, and wearing long clothes, was recovered a few yards away from the spot where her mother’s body had first been seen.

When the ambulance arrived, the bodies were taken to the mortuary at Pillgwenlly. Word had spread in the neighbourhood, and by the time the procession reached the Marshes Road, it had garnered a small following. By the time they reached the High Street, the crowd had grown quite large.

At Pillgwenlly police station (in the same building as the mortuary) the bodies were examined. Both mother and child were respectably dressed, in warm clothes, as was fitting for the weather, and the young woman was wearing gold earrings, a gold brooch, a gold wedding ring, and a keeper ring. In a pocket they found a handkerchief with the name ‘E. Chambers’ in one corner. For a few hours her identity remained unconfirmed, but at about 12 o’clock, Charles Chambers arrived. Overcome with grief, he identified the bodies of his wife Emily Louise Chambers, and his six week old baby Eva Louise.

Charles and Emily were well known Newport residents, who lived at 14 Tunnel Terrace. Charles was a clerk who had been employed for many years by Mr Thomas H. Howell, a prominent iron, steel and oil merchant in Llanarth Street, and a councillor for the North Ward since 1888. Charles was very well thought of by Mr Howell and had earned his complete confidence and respect. Emily was aged 32. She was born in Newport and her maiden name was Morgan. At the age of 17 she had been working as a servant at the Gold Tops Vicarage, and shortly before her marriage she had lived at Pentonville, Newport. Charles and Emily had married in 1886 and had five children. Frank was born in 1887, Reginald Tinson in 1889, Gladys Mary in 1891, Charles Trevor in 1895, and the baby, Eva Louise, in December 1896.

It soon became evident that Charles and Emily had been through a terrible time in recent months. Little Charles Trevor had died seven weeks ago, aged one year, just before Eva was born. Another child had been ill for eleven weeks and was now suffering from the after-effects of an operation. Another child had just recovered from a severe attack of scarlet fever, and another was a patient in the isolation hospital for infectious diseases at Allt-yr-yn, suffering from the same disease.

Emily was up all Thursday night with baby Eva, however, at half past eight, when her husband was preparing to leave for work, she had not seemed unusually depressed. She asked her husband to come home at about noon, when the doctor would be there. After Charles’s departure she was left alone in the house with her children and her servant, Anne Lewarne. Emily told Anne to get the room upstairs ready for the doctor, and almost immediately after this, she left the house. It was thought that Emily had made her way through Devon Place and over Queen’s Hill to the canal. It was suggested that she was heading to Allt-yr-yn Hospital to visit her child, and had slipped into the canal, unbalanced by the high winds and the mud or ice underfoot.

This was not, by any stretch of the imagination, the most logical route to the hospital. There was a footpath which was much more direct. However, the good people of Newport were keen to avoid any suggestion that this beleaguered young woman had taken her own life. In those days English and Welsh law perceived suicide as an immoral, criminal offence, both against God, and against the Crown. It was not until 1961 that suicide ceased to become a criminal offence. Charles and Emily were a respectable couple, and it would have been considered important to protect their reputations.

The inquest took place before Mr Lyndon Moore, borough coroner, at the Town Hall, Newport, on the following Monday evening. Charles stated that he left his wife at about 8.50 on Friday morning, and did not see her alive again. There had been trouble and sickness in the house; the children had diphtheria, and one had died about two months earlier. Naturally, Emily was depressed, but no more than she had been over the last few weeks.

“Had your wife any delusions or illusions?” the Coroner asked.

“She thought she was suffering from diphtheria,” Charles replied, “and that there was something radically wrong about her throat. She was examined by Dr. Garrod Thomas, who told her she was mistaken. I went home about 12 o’clock, and found that she was not at home, and half an hour later I was told she had been found in the canal.”

“Had your wife ever talked about committing suicide?” the Coroner asked.

“Not to my knowledge,” answered Charles.

“As a matter of fact, the children were going on all right?” asked the Coroner.

“One was. One had been to the Altwyn Hospital, and had returned, and was going on all right.”

“There was no reason to apprehend anything fatal to the children?”

“No,” replied Charles. “Between one and two o’clock I received this note, which the servant, Anne Lewarne, found on the mantlepiece.”

The Coroner read the note aloud to the jury.

“Dear Charlie, My grief seems more than I can bear. I have prayed and prayed for help, but it does not come. It is all getting worse. Baby is ill now, and I am choking. With my love to your children, may God bless you.”

The Coroner asked, “Is that your wife’s handwriting?”

“It is.”

“That choking refers to her belief that she had diphtheria?”

“Yes.”

“As a matter of form, you were on excellent terms?”

“Yes, I parted on the best of terms that morning – we always did.”

Finally the Coroner established that Emily and the children’s lives were not insured.

Next to be questioned was Anne Lewarne, the servant. She said that at quarter to 9 on Friday morning, her mistress told her she was going out for a little while, and that she would not be away long. She had only been out so early once before. She had left a note, but Anne did not find it until 2 o’clock. The Coroner asked whether Emily had ever talked about committing suicide.

“No,” replied Anne, “she had been rather dull from the trouble.”

“She was perfectly happy with her husband?” asked the Coroner.

“Perfectly. When she went out I did not know that she had taken the baby.”

“Had she been to bed the night before?” asked the Coroner.

“From what I heard afterwards, she had not. Mrs Lockyer, a neighbour, had been sitting up with her because of the sickness of the baby. I could not say she had much rest of late. She complained to me that she couid not sleep.”

“You know she had this mistaken notion about having diphtheria?”

“Yes, she said she thought she had it all the time.”

James gave evidence next. He said that he had seen a woman carrying a baby proceeding at a rather fast pace along the towpath, and that half an hour later he heard that the bodies had been found drowned, 50 or 60 yards on from the spot where he had seen her. John Jones then gave evidence that he had seen the bodies and had given the alarm. William Price said he got the boatman’s hook and pulled the bodies ashore. They rubbed the woman’s hands but they were soon convinced that she was quite dead, and neither of the witnesses made any effort to resuscitate her (referred to as scientific resuscitation).

Dr. Garrod Thomas next confirmed what Charles had said about the illness in the house, and said that for the last month he had attended once or twice a day. Every time he went, Emily had asked him to examine her throat, and once when he did not do so, she called him back. She also thought the baby had diphtheria. He had examined little Eva only on the day before her death, and had found nothing the matter. It was purely a delusion.

It probably says something of Charles and Emily’s standing in the community that the Coroner generously pointed out that there was no conclusive or convincing evidence that Emily had thrown herself into the canal. He said that it was quite clear that her mind was unsettled by the many troubles which had befallen her, and equally clear from the evidence given by Charles, Anne the servant, and Dr. Thomas, that she was under the delusion that she had diphtheria. The jury took his direction and returned an open verdict of ‘Found drowned’, there being no evidence to show how Emily and Eva ended up in the canal. They joined the coroner’s in expressing great sympathy with Charles.

“Thank you,” Charles said.

If only Emily had known that her other children would survive, how different the family’s fortunes might have been. Later Charles’s unmarried sister Mary Jane came to live with the family, and later still his widowed mother. Charles remained working for Thomas H. Howell. When Charles’s employer Thomas Howell died in 1928 he left £150 to Charles. Charles died in 1949.

Rest in peace, Emily and Eva.

Sources:

Portsmouth Evening News – Friday 22 January 1897

Western Mail – Saturday 23 January 1897

Western Mail – Tuesday 26 January 1897

Cardiff Times – Saturday 30 January 1897

Gloucester Journal – Saturday 14 January 1928

Genealogical research.

Notes:

I have not yet identified James. I found a James Hodges who was a bricklayer, but in 1901 he lived in Frederick Street.

A keeper ring was a simple close fitting ring worn to prevent another more valuable ring from sliding off the finger.