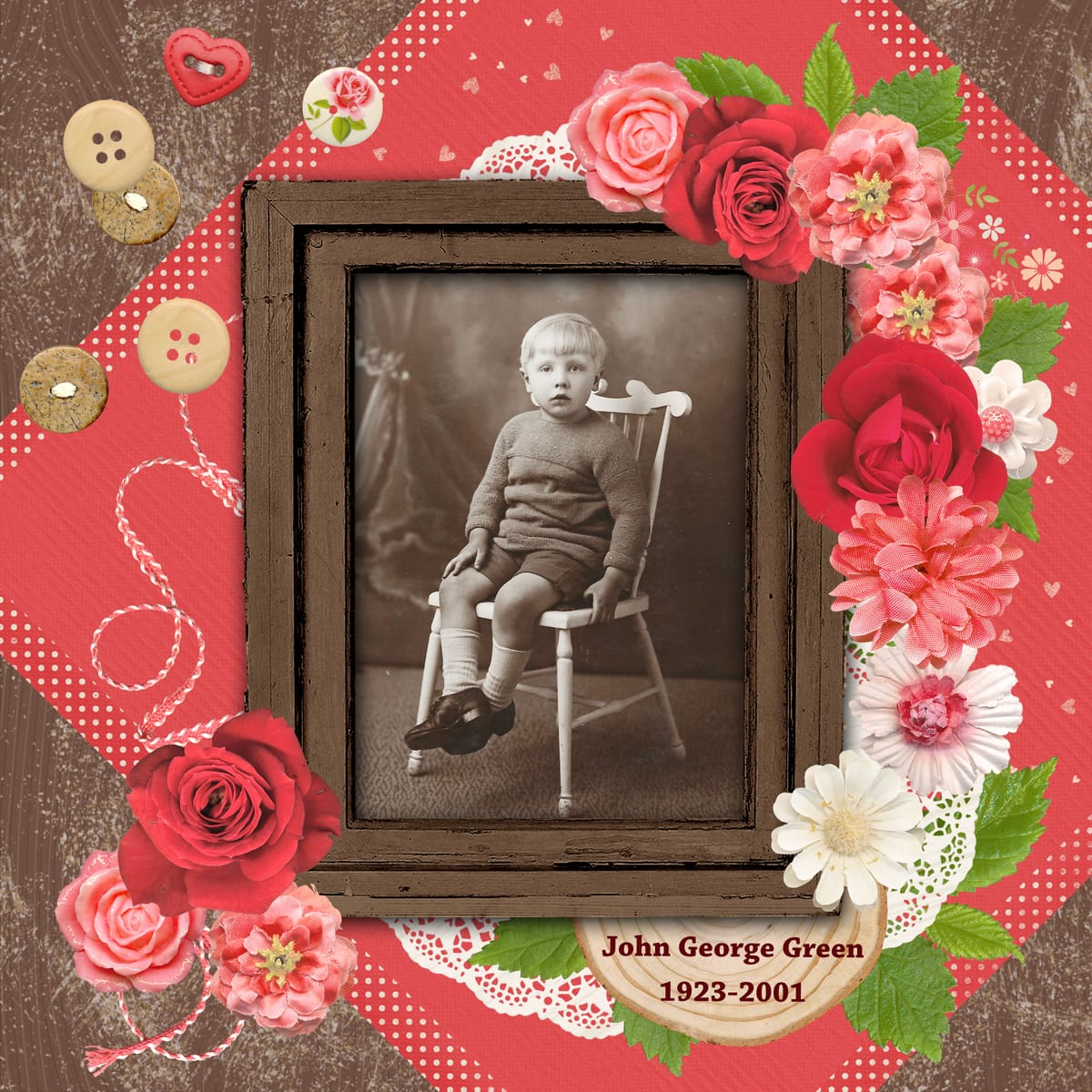

John George Green, 1923-2001, #2

My father, John George Green, was born on 9th August 1923 in Deptford. He had two brothers, Dennis and Leslie, and a sister, Betty.

John George Green was born on 9th August 1923 in Deptford. He had two brothers, Dennis and Leslie, and a sister, Betty.

He took an early interest in engineering. Here's his Hornby train set!

John went to Charlton Manor School, and became a keen footballer, but his favourite game was cricket. His team were the local league champs in 1934.

John passed the 11+ entrance exams for the Grammar School, but his father insisted that he went to work. He was Top Boy of Fosdene Road LCC SB School. 'Thoroughly deserves this position' was written on his school report.

John started work in the office of J Stone and Company Ltd, Deptford, aged 13 years 11 months.

In 1937 John decided to become an engineer and started an indentured apprenticeship within J Stone and Co. He worked six days a week on a mixture of day and night shifts, in a variety of workshops, tool shops and fitting shops, usually working for 12 hours straight.

Three times a week, John studied at evening classes at the South East London Technical College (SELTI) towards the examinations of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, London. In his first year he studied elementary technical subjects, English, technical drawing, and trade calculations. These studies gave him credits towards more advanced studies in production engineering, mathematics, applied mechanics, mechanical technology, engineering science, machine design and construction. His examination results were vetted by J Stone and Co.

John applied himself diligently to his homework during the week, but on Saturday evenings and on Sundays he enjoyed a busy sporting life, playing cricket and rugby in season, including a spell at Westcomb Park, and cycling with the Eagle Cycling and Social Club at Charlton. It was here that he became friends with his future wife, Margaret Whitehead. Sometimes he found time to meet her on Saturday evenings to go ballroom dancing at the Greenwich Town Hall.

John’s apprenticeship continued throughout the War, so he was not required to serve in the forces. He was a member of the Home Guard at J Stone and Company, and often took part in fire watching shifts.

One day, when tarring a moving belt on a machine, John’s shirt sleeve was caught and pulled into the mechanism. His arm was badly damaged with a compound fracture. The nurse on duty in the first aid room splinted his wounded arm and he was driven to the local hospital. After one operation in London he was evacuated to the Southern Hospital in Dartford for a skin graft. The Southern Hospital was a major facility for the treatment of war casualties and air raid victims, including a large contingent of naval ratings and army and RAF personnel who had been injured. More casualties from Dunkirk (26th May to 4th June 1940) were admitted to the Southern than to any other hospital in the UK. During his three and a half months of hospitalisation John met one of the servicemen who had lost an arm at Dunkirk, then on the boat being evacuated back to England he had also lost a leg. It made John thankful that he still had his arm, could move his fingers, and was able to continue with his apprenticeship and his sport.

John taught himself to write with his left hand while he was recovering. His handwriting was never the neatest (even his right handed writing was sometimes hard to read), so for the rest of his life he often wrote in capital letters to ensure that his writing was understood.

John soon managed to make up for lost time at his evening classes and he sat his exams as planned. In his second year at SELTI he continued with mathematics, engineering science, applied mechanics, heat engineering and engineering drawing. In his third year he continued with mathematics, applied mechanics, workshop mechanical technology and strength of materials. All of the subjects he studied were supplementary endorsements to the Ordinary National Certificate.

In 1943 or 1944 the house in Indus Road, Charlton, where John lived with his parents and siblings, was bombed out, and the family lost everything they owned. They went to live in temporary accommodation, a council house furnished with reclaimed possessions of victims of the war.

By 1945 John had completed his Higher National Certificate examinations, and Margaret was training as a VAD nurse, making plans to go to India. One day during her embarkation leave John invited Margaret to a friend's party. Soon after this he turned up unexpectedly to see her. Margaret wrote in her autobiography: 'We were always good friends and had never dated each other, often what arrangements we did make were with a group, either cycling or dancing. He told me in a very matter of fact way that he had just been walking down by the river, which was a most unusual thing for him to do. While there, he was busy thinking that our marriage couldn't be based on anything more perfect than what our friendship had been in the past. I smiled and said, "That sounds a very good business proposition".'

The wedding plans were put on hold, and John continued to work through the various departments of J Stone, until 1947 when he reached the Drawing Office. He married Margaret on her return from India early in 1947.

John was promoted at the age of 23 to Stone Platt, a factory in Oldham, Lancashire, where he was in sole charge of the Drawing Office. John and Margaret bought their first home at 16 Brookside Avenue, Grotton, Saddleworth, and lived there for three years. John supervised the transfer of the company’s Ships’ Davits and Windows manufacturing from London to Lancashire, acting as Liaison Section Leader. He continued his studies at Oldham Municipal Technical College and Manchester College of Technology, gaining his National Certificate in Mechanical Engineering Higher Grade.

Meanwhile John played rugby for Oldham Rugby Union Club, and got a mention in the newspaper most weeks for his outstanding play as a forward. His wife used to recall that the team played games against the Harlequins and the Wasps.

John was promoted yet again to become Joint Works Manager at another J Stone and Company subsidiary, Bulls Metals and Marine, at Clydebank, Scotland. John and Margaret moved to 'Charlton', Cochno Road, Hardgate, Dunbartonshire. The company was famous for its 30 ton plus ships’ propellors, water tight doors, and davits. John transferred his department of Ships’ Davits and Windows there. Examples of their work were to be found on many ocean liners, including the Royal Yacht Britannia. In the course of his work John boarded and sailed on many of these ships.

John continued with his rugby, playing for Kelvinside and west of Scotland Rugby Club. Their first two children, Lesley and Stephen, were born in Scotland.

John continued his studies at The Royal Technical College in Glasgow. He was a member of the three man committee of the Glasgow University, studying Business Methods and Administration, Financial Control and taking classes for young executives with Professor Cairncross. John also attended public speaking classes and regularly attended meetings of the British Institute of Management. He gave some lectures at the university. In 1951 John was elected a Graduate of the Institute of Mechanical Engineering, and in 1955 he was awarded Associate Membership, his well-deserved reward for 18 years of self-disciplined study and perseverance.

In November 1957 John was offered the chance to be Works Manager at J Stone and Co at Taratulla Road, Behala, Kolkata, in India. John, his wife Margaret, their son Steve, then aged 5, and their daughter Lesley, aged 7, all moved to India, where they lived in a company bungalow.

There were over 400 employees in the Kolkata factory, all Indian or Anglo-Indian. This factory specialised in electrical railway equipment including dynamos for train lighting, control gear, fractional horsepower motors, braking systems, coach couplings for electrical supply, fans and air conditioning, and various accessories for coaches. John increased production at the factory by 100%. Still committed to sport, he started a tennis club for the employees, which held competitions against other employees. In 1959 the Indian government was increasingly demanding the ‘Indianisation’ of British manufacturing concerns. John was obliged to hand his job to the Indian financial director’s niece's husband.

John returned to England with his family in 1959, and decided to take the opportunity to make a break from J Stone and Co after 22 years of service. The family settled in Woodlea Drive, Bromley, Kent, and in 1961 John’s youngest daughter Sheridan was born.

From 1960 to 1962 John was Works Manager for Venesta Foils, a rolling and converting plant at British Aluminium’s Silver Town in the East End of London. The Managing Director was Oliver Philpott, one of the three prisoners of war who famously escaped from Stalag Luft III by tunnelling under a wooden vaulting horse. When the American company Reynolds Virginia bought Venesta Foils, they installed their own American executives. Both John and Ollie lost their jobs, but John’s replacement, Ed Miller, and his wife Jean, became lifelong friends. During retirement John and Margaret visited their home in Virginia and shared a fabulous 1000-mile tour of America with them.

Now aged 38, John was eager to fulfil his ambition to be a the peak of his career by the age of 40. He was offered a job managing Rayner Optical Company, a small company that was then running at a loss. Rayners owned a chain of opticians all around England, and a factory in Hove on the South Coast. John remarked that this would be like semi-retirement for him. Certainly John enjoyed his leisure time at the factory. He was a frequent participant and trophy winner in company table tennis and snooker competitions, but working at Rayners was far from the quiet life he might have expected.

The factory made lenses and as a sideline, gemmological instruments, but it was also conducting pioneering work in the manufacture of intraocular lenses, as surgeons developed their sight saving cataract surgery. Working with John, the surgeons designed new types of lenses, using computer-aided design to develop their products. Over the years John developed this department until eventually he built a brand new ‘clean air’ factory, Rayner Intraocular Lenses, supplying customers worldwide. John was awarded the Councillorship of the Association of Dispensing Opticians in recognition of his work in this field.

John also worked with the Gemmological Association of Great Britain to found Gemmological Instruments Ltd., a company for which Rayners were the sole manufacturer of various instruments including Diamond Testers, Refractometers, Spectrascopes, Polariscopes, Dichroscopes and Scopelights.

John was invited each year to Goldsmiths Hall to present a Rayner Refractometer to the top examination student. Afterwards, he and Margaret joined the Directors of the Gemmologists Society at a dinner in the Hall, with its glittering chandeliers, gold plates lining the walls, and the Goldsmiths work decorating each table.

During John’s years at Rayner and beyond, he served on a number of boards and committees.

- East Sussex Fire Liaison Committee

- West Sussex Employers Network

- East Sussex Employers Network

- ECRO - Engineering Council Regional Organisation for Kent and Sussex

- Engineering Council Careers Committee

- East Sussex Industry Links (links between education, commerce and industry)

- Training and Enterprise Council

- Crawley Enterprise Council

- SATRO - Science and Technology Regional Organisation

- Sussex University Industry Committee

Perhaps his most valued positions were to be Chairman, then President of the Federation of Sussex Industries and Chairman of the South East Region of the Confederation of British Industries.

John retired in 1988, aged 65, but remained on the board of Rayner and Keeler, the parent company, and continued to serve on many committees.

He also filled his days with a new role as a Governor of Blatchington Mill School. Margaret persuaded John to take some memorable holidays, in South Africa, New Zealand, America and the Caribbean, where John benefited greatly from the relaxed atmosphere and the convivial company. He particularly enjoyed his last holiday, a short visit to Iceland, a long held ambition, with his son Steve.

John developed some enthusiastic hobbies during retirement including picture framing (to keep up with Margaret’s prolific altistic output!) and silversmithing. As a young man John had shown some skill in marquetry, and now he uncovered a singular talent for woodcarving.

Sport still played a large part in John’s life. Both John and Margaret enjoyed playing golf, and they also played croquet to international competitive level. In his final years at home, when competitive sport was no longer a possibility, John loved pitching cricket balls and putting golf balls with his grandchildren in the garden.

His last great pleasures were accompanying Margaret on her duties at The Grange, a delightful Art Museum in Rottingdean, where he found many friends to talk to, and his daily walks in the village and on the seafront.

In his final years in Oakhurst Court Nursing Home, John was well looked after. His children felt that even though the father they once knew was steadily eroded by his illness, the traits that persisted in those final years represented the foundation of his character. It is significant, then, that he was remembered at the home, as he was by his many friends and colleagues, as a kind, polite, honest man with a great sense of humour.

John’s commitment to his work was such that he early in their life together he warned Margaret, 'Work comes first, my wife comes second'. Alan Dixon, Financial Director of Rayners, remembered John as a good man who always looked after his workers. He also had a cheeky sense of humour. Sheridan kept one of his work notebooks in which he had pasted a favourite quote, 'Do carry on, I'm a great bullshitter myself, but I like to listen to an expert'.

John proved over the years that he was a man who adhered to traditional family values, and that in many things he put his family’s needs before his own. He was a disciplinarian, especially with his son, but it was always John, not Margaret, who would give the girls support and cuddles when they were needed. He was passionate about nurturing enthusiasm in young people. Nothing would have given him more pleasure than to know that his three children and five grandchildren would benefit from his efforts, and that they truly appreciated all that he did for them.

You can find out more about my father's life in my mother's memoirs, Greenwich Girl.